Let's start off with a simple little connect-the-dots puzzle. You might have seen it before, but if you haven't, definitely give it a try!

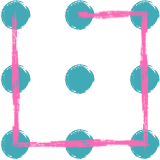

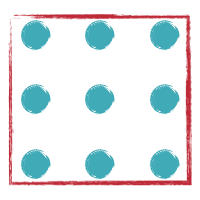

Below are nine dots arranged in a neat little grid. The goal is simple: Connect all 9 dots with 4 connected strokes!

- Tap once in the area below to start a line

- Tap somewhere else to finish that line

- Tap again to create a connected line

- You only get 4 lines. Try to connect all 9 dots!

Let's solve it.

Permalink to "Let's solve it."If you've never seen this 9-dots puzzle before, it can be frustrating at first.

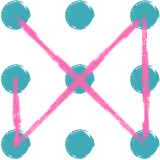

Let's try a few strategies here...

Darn! None of these patterns work. No matter what we do, it feels like we need five lines, not four.

Ok, so how do we solve this puzzle?

Well, let's think carefully about the rules of our little game first:

- Without lifting my pencil from the paper...

- I must draw four straight lines...

- Which connect all nine dots in a 3x3 box.

Seems simple enough. Except something feels a little wrong here. What were the original instructions again?

Connect all 9 dots with 4 connected strokes!

Hmm, the official instructions seem quite a bit different from the rules I just enumerated above. Did we perhaps assume too much?

Let's pick apart our assumptions one bit at a time.

- Without lifting my pencil from the paper...

- I must draw four straight lines...

- Which connect all nine dots in a 3x3 box.

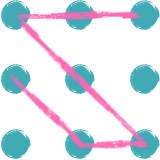

The nine dots are arranged in a 3x3 box. However, do our lines need to stay inside of this box? What if we allow the lines to go a little outside the confines of the grid...

Ah ha! And just like that, we can connect 9 dots with 4 connected lines. We just needed to think outside the box.

Cool, the puzzle is solved! We're done now, right? Perhaps, but we made an awful lot of assumptions early on. Are there any more assumptions we can challenge? Maybe there's more than one solution...

- Without lifting my pencil from the paper...

- I must draw four straight lines...

- Which connect all nine dots in a 3x3 box.

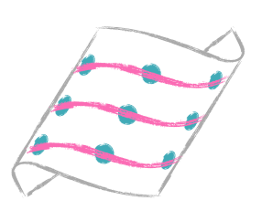

Usually this problem is given on a piece of paper. However, does the paper need to be flat? What if we curl the paper up and use the third dimension to our advantage? We can curl the paper into a spiral tube and draw a single line that wraps around the tube, intersecting all nine dots:

Wait, you mean this puzzle can be solved with just one line? Indeed! We just needed to think beyond two dimensions.

We're not done yet though! Is there at least one more assumption we can tackle?

- Without lifting my pencil from the paper...

- I must draw four straight lines...

- Which connect all nine dots in a 3x3 box.

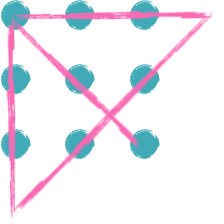

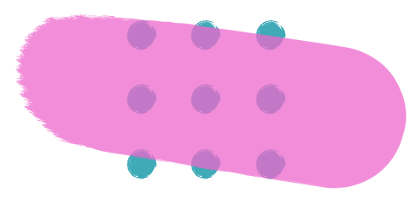

Why constrain ourselves to a particular tool? Do we need to use a pencil? What if we use a paintbrush instead...

Perhaps this is not a solution intended by the original author of the 9-dots puzzle, but it definitely meets the original criteria of "connect all 9 dots with 4 connected strokes". It's easy to make the assumption that we must use thin lines to solve the puzzle because, frankly, the puzzle is too easy if we allow a giant, thick line.

But in making this assumption, we lose out on the simplest solution!

Perceptual Blockers

Permalink to "Perceptual Blockers"The 9-dots puzzle is a classic (if not the classic) example of a thinking-outside-the-box puzzle. For those unfamiliar with the problem, it feels impossible to solve. But once you discover the solution(s), the answer seems obvious.

So why wasn't the answer obvious to begin with? Why did we need to think outside the box to solve the puzzle?

What we have here is an example of perceptual blockers to creative problem solving. Perceptual blockers are obstacles that hinder the problem solver from seeing the necessary information needed to solve the problem. Perceptual blockers can also prevent the solver from seeing the entire problem to begin with.

The 9-dots puzzle is a perfect example. The nine dots are arranged in a box. That box creates an invisible barrier, and this makes people think the lines must be contained within the barrier.

Now, this page presents the puzzle with an actual visible barrier for the simple reason that the interactive area needed to be clearly defined. However, this time the dots themselves may have been a perceptual blocker. People like to click on objects rather than whitespace, so it is more tempting to only ever click on the dots. Yet to solve the puzzle, you must click on the whitespace!

Because of the way the problem is framed, it is more difficult to perceive the different possibilities.

- The 3x3 grid creates an invisible box, making it hard to see that we can use the space outside.

- Papers are usually flat, making it hard to see we can roll it up.

- If we're given a pencil, we might not think to use a paintbrush.

A problem’s context can prime the brain into searching a narrowed solution space.

Unassuming Assumptions

Permalink to "Unassuming Assumptions"Assumptions are one of the primary sources of perceptual blockers. Unfortunately, they tend to be rather unassuming, meaning it can be very difficult to recognize when we are making adverse assumptions. Often, assumptions can be disguised as actual problem constraints, making them even harder to identify.

Fortunately, there's a tool we can use to help us un-assume these assumptions. I affectionately call it Unassuming Assumptions.

There are three simple steps:

- Write down all the rules and constraints of the problem in as much detail as possible. Include literally everything that comes to mind.

- Circle any single phrase or constraint.

- Ask yourself a question contrary to that constraint.

For example, when we were describing the 9-dots problem, we noted that the dots were arranged in a 3x3 box. We highlighted the phrase "3x3 box" and asked ourselves a contrarian question: Do we need to stay in the box?

This is an exercise in divergent thinking, allowing us to expand the scope of the problem in order to unearth potential solutions. But how can we be expected to write down all our assumptions when our assumptions are hard to identify in the first place?

The reason is because assumptions tend to be left unsaid. By forcing ourselves to say everything, we may invariably put to light assumptions we've been making the whole time. And once they are on paper, it becomes easier to question them.

Summary

Permalink to "Summary"The 9-dots puzzle is classically used to demonstrate the concept of thinking outside the box, but I also think the puzzle is a superb demonstration of the realness of perceptual blockers in problem solving. The way a problem is framed tends to lead us into making assumptions that we don't have to make.

For a real life example, how can I go and get groceries when my car is unable to start? Already I made the assumption that I have to "go" to obtain groceries; what if I instead placed an order online?

Next time you are trying to solve a difficult problem, try using the unassuming assumptions technique described above and see if you gain any new insights!